Does the “formula” below make any sense to you?

D2D + PAYT + DRS + MWS = +90%

Most scientists or mathematicians would laugh at the idea of that being any sort of formula or equation. It’s full of jargon-based acronyms related to the field of waste, but we believe that this is a formula that can have a dramatic impact in Europe’s battle to reduce our mixed (non-recycled) waste and subsequent Greenhouse Gas (GhG) emissions from the waste sector.

So let’s explain what this is in a bit more detail and why it can have such a positive impact.

D2D = Door to door collection. Within European waste management today, it is clear that collection models which operate by collecting several separated waste streams from the doorstops of households and businesses deliver the best results. Separate collection is mandated by European Union law and includes the collection of separated paper/cardboard, plastics/metals/drinking containers, glass and waste oils – with the last two often collected in street containers or at specific collection points, rather than from the household for operational reasons. From 2024, it will be mandatory to collect organic waste separately and from 2025, textiles and hazardous waste will also be required to be separately collected.

We have vast amounts of evidence from our Zero Waste Cities built over the last 15 years, that door-to-door collection models bring the best performance in terms of the quantity and quality of recyclable material collected. As our recent research has shown, these models also deliver the best results for organics specifically, which in turn have a positive knock-on effect on the wider system.

With effective door-to-door collection of these materials, supported by some educational awareness activities, municipalities can establish a system to easily surpass the minimum required targets for recycling – 55% by 2025, 60% by 2030, and 65% by 2035.

The next step in the formula is to add Pay-As-You-Throw (PAYT). PAYT models are ones which individualise the waste costs for every household in proportion to the amount of waste generated (and in particular to the amount of residual waste to be disposed of at landfills or incinerators) so as to incentivise waste reduction. The best PAYT models include the following within their yearly waste fee:

- A fixed part that all households must pay (around 60-70% of the overall fee);

- And a variable part (the remaining 30-40%) that gets defined in proportion to the volume of waste (e.g. number of set-outs, volume of waste bins or frequency of collection adopted by each household). Households which generate less waste and therefore have smaller bins or put their bins out pay less.

Evidence from our work with European municipalities shows that the cities which are separately collecting the highest totals are those which implement this kind of Pay-As-You-Throw model. Even at Municipalities with previous excellent achievements in separate collection thanks to implementation of D2D schemes, introducing PAYT further boosts recycling rates and typically halves the amount of residual waste. These municipalities are regularly separately collecting in excess of 80% of the municipal waste generated. The Italian city of Parma is the most notable example of how this can have such a positive impact, in a short amount of time and is possible within a densely populated area.

%22%20transform%3D%22translate(1.6%201.6)%20scale(3.125)%22%20fill-opacity%3D%22.5%22%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23f1f1f1%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(-58.23144%20-24.96196%2015.97282%20-37.2615%20216.8%2027)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23b3b3b3%22%20cx%3D%2269%22%20cy%3D%2212%22%20rx%3D%2275%22%20ry%3D%2275%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23f1f1f1%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(4.08895%2036.42373%20-63.86511%207.16954%20112.2%20113)%22%2F%3E%3Cellipse%20fill%3D%22%23b4b4b4%22%20rx%3D%221%22%20ry%3D%221%22%20transform%3D%22matrix(39.95116%2026.54349%20-23.77482%2035.78399%20216.4%20109.5)%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E) Visual from Zero Waste Europe’s #GetBack campaign, advocating for a transition to reuse systems.

Visual from Zero Waste Europe’s #GetBack campaign, advocating for a transition to reuse systems.

Onto the third piece of this formula, which is Deposit Return Systems (DRS). DRS has been proven to be the most effective and sustainable way to retain the value of materials over and over again, with recycling as a last resort. A DRS is a system whereby consumers buying a product pay an additional amount of money (a deposit) that will be reimbursed upon the return of the packaging or product to a collection point. The system is based on offering an economic incentive for consumers to return empty containers to any shop to ensure that they will be reused or recycled.

For beverage containers, these systems are already operating in more than 40 regions worldwide with great results. For now, DRS offers municipalities a proven methodology for capturing close to 90% of beverage packaging consumed, which is the target required by EU law for 2029. Ideally, DRS should prioritise reusable glass containers, but they can also be used in the short/mid-term to capture recyclable PET bottles. Therefore, when DRS is in operation locally, on top of existing D2D collection and PAYT for households, they can result in much further progress being made towards the minimisation of mixed waste.

So, now we move onto the final piece of the formula as we seek even better results…

Mixed waste sorting (MWS) is a final stage solution for recovering recyclable materials such as plastics, metals and paper before the remaining mixed waste is incinerated or sent to landfill. MWS acts as a recovery backstop for recyclable materials that are not captured in either the municipal separate collection system or any deposit return system (DRS) in place. Such recyclable materials may still be found in residual waste for several reasons – perhaps due to the inherent imperfection of separate collection systems, or due to the fact that many of such materials are not covered by Extender Producer Responsibility (EPR)propelled separate collection schemes. This is, notably, the case for non-packaging plastics, which are often made of valuable polymers and which concentrate in residual waste. In municipalities with high recycling rates and subsequently low amounts of residual waste, the percentage of such plastics is much higher.

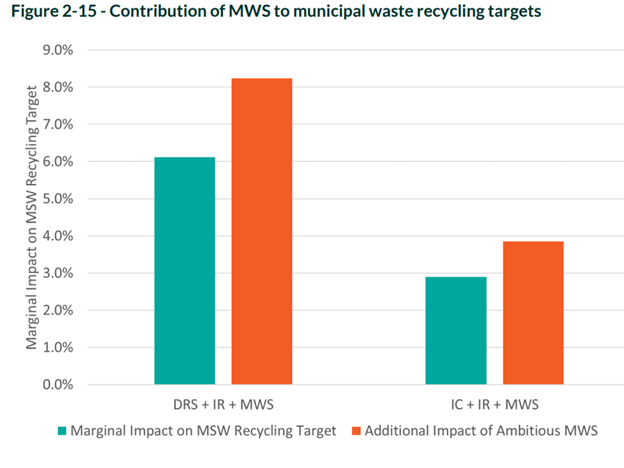

Graphic taken from Eunomia and Reloop report on mixed waste sorting. IC refers to improved collection and IR refers to improved recycling.

Technological advancements today mean that an increasing number of waste companies in Europe have access to automated sorting equipment to separate these materials from the residual waste, and then clean them to a standard which means they can then be easily put back into the secondary material system. With its focus on plastics and metals, mixed waste sorting can have a dramatically positive impact on reducing climate emissions for municipalities that incinerate their waste especially.

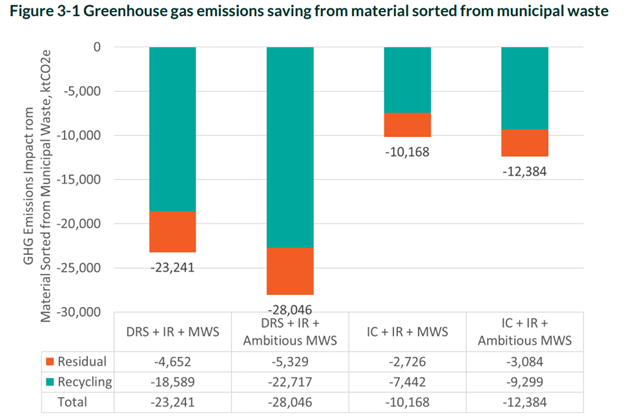

Graphic taken from recent Eunomia and Reloop report on mixed waste sorting, looking at the GhG emission savings from different collection models.

Therefore, when combined together, this is the winning formula for municipalities who wish to reduce their mixed waste.

With the foundation of a door-to-door collection system in place, supplemented further by Pay-As-You-Throw to further incentivise waste reduction by citizens, municipalities can achieve separate collection rates in excess of 90%, with nearly over a hundred examples of this from Italy. Still, mixed waste sorting may be added in at the end as a final backstop to collect the recyclables missed before, or not targeted by separate collection schemes, as in the case of non-packaging plastics.

The key thing to remember is that without any one of the three parts of this equation, the high performance results are much less likely to be achieved. As we see from examples in Sweden and Norway, municipalities that adopt only mixed waste sorting are not able to achieve results above 60-70%, whilst the EEA has identified a number of barriers preventing European countries from increasing their recycling rates.

Of course it is key to acknowledge here that better separate collection is not the magic bullet to solve our problem. We must first tackle waste generation as a whole, given the struggles of Europe’s recycling system for plastics. This can be done by municipalities implementing policies and measures that help embed a reuse culture.

However, while reduction and reuse are still the “Plan A” for sustainability, recycling continues to be the low-hanging fruit of the circular economy, and may provide key services and benefits while we pave the way to more reduction and reuse. Therefore, by separating as many of the recyclable materials as is possible, with the result of this being each material is of a higher quality and therefore more likely to be recycled in a closed-loop, municipalities can have a huge impact on the volume of waste that ends up being burnt or landfilled – with the subsequent benefits (both economic and environmental) this brings.