COP27, being hosted by Egypt, marks the 30th anniversary of the adoption of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992. As a global society, we are rapidly approaching the limit of our carbon budget necessary to keep global warming at 1.5C. Therefore COP and other international events are crucial to ensuring that countries play their part. Climate change mitigation is essential to avoid a potential breakdown of global ecosystems. Mitigation refers to reducing the impacts of climate change through preventing or reducing emissions. This is done through interventions which reduce the sources of Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and/or enhancing sinks. Adaptation rather focuses on anticipating the adverse impacts of climate change and taking appropriate action to minimise damage. Mitigation reduces the impact of climate change, while adaption reacts to them as they come.

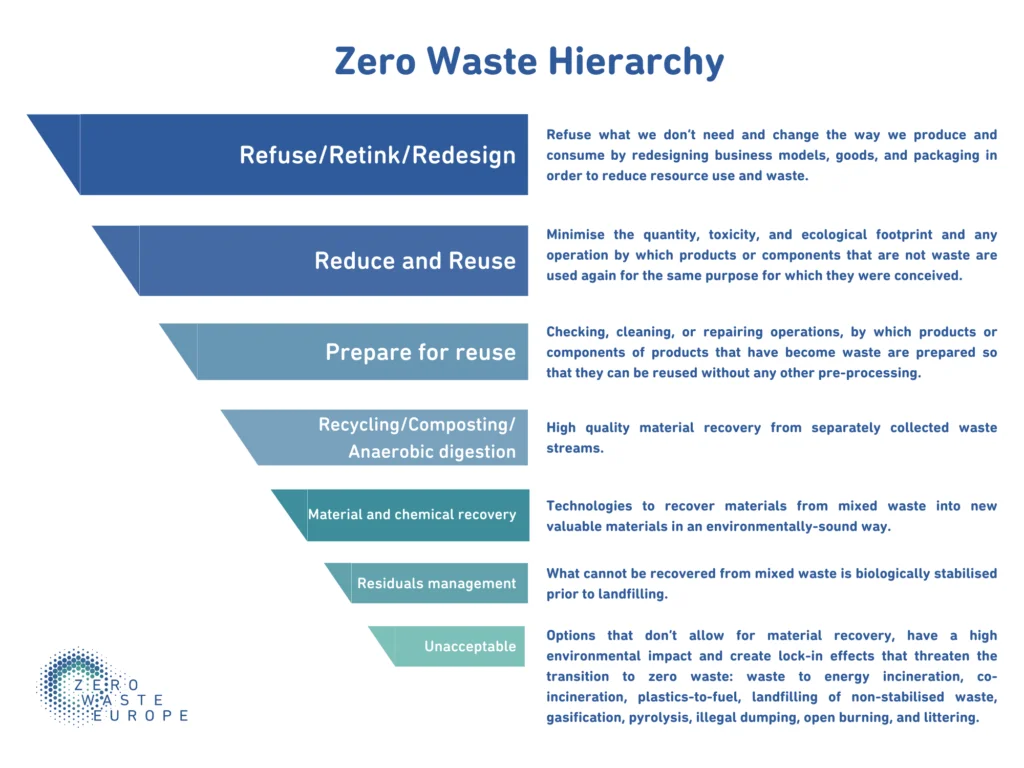

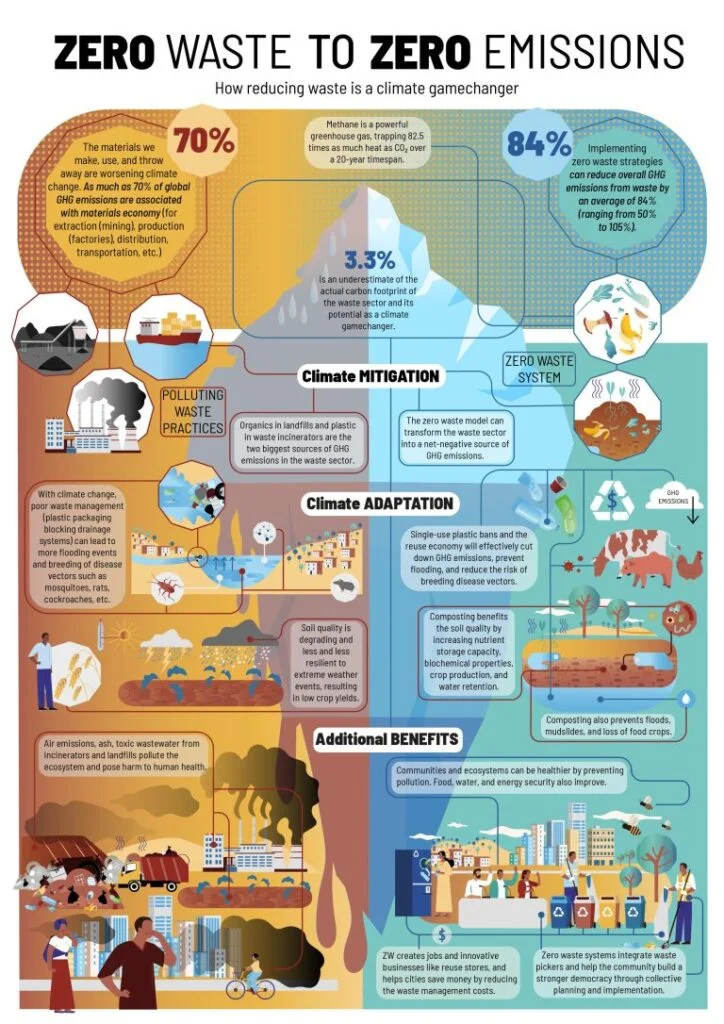

Waste prevention is ultimately a form of climate change mitigation, as it avoids emissions throughout the lifecycle of materials. According to the waste hierarchy, prevention is the most preferable option in waste management, as waste is not produced in the first place , and the environmental impacts that come with trying to find a suitable destination for waste are avoided. Over 70% of global GHG emissions come from the material economy, all the way from extraction to disposal. It is therefore a climate imperative that waste prevention is a primary focus. If waste is prevented, the waste management sector can provide more than 100% emissions reductions, as the need for new materials is averted in supply chains, reducing emissions throughout the whole lifecycle of products.

Food waste and plastic are two uniquely problematic waste streams and present a valuable case study into the powerful impact of waste prevention on climate change mitigation. Plastic waste, if left untreated can persist for thousands of years, leaking chemicals into the environment, with long-term impacts for ecosystem and human health. In Europe, food waste amounts to roughly 180kg per head per year, totalling 20% of all food produced.If these losses were a country, they would be the 3rd biggest GHG emitter in the European Union (EU).The primary reason for this is that organic waste, especially food, emits a significant amount of methane – a GHG which has over 80 times the climate impact of carbon dioxide. Food waste prevention requires a holistic approach from production, distribution and consumption. At the local level, municipalities can act holistically to create local sustainable food systems that reduce food loss at the primary level, through incentives that promote shorter supply chains and bio-waste management systems that ensure food waste is valorised into fertilser, in cases where it cannot be prevented, among others.

Plastic waste comes with its own uniquely pernicious impacts. Plastic production comprises a significant, and growing, share of the global carbon budget, standing at 1.7b t/CO2e, projected to rise to as much as 6.5b t/CO2e by 2050. If this trajectory continues, emissions from plastic alone could swallow up more than a third of the remaining carbon budget for a 1.5C warming target. Primary plastic production is inextricably linked to fossil fuel production, as 99% of plastic produced today is done through fossil fuels. Whereas litter such as paper will persist in the environment for a matter of weeks, plastic beverage bottles can persist for almost 500 years, entering ecosystems and the food chain, with proven health impacts associated with chemicals found in plastic packaging. While mechanical recycling of plastic can replace virgin plastic production and the associated fossil fuel use, only a fraction of discarded plastic can be captured and recycled effectively, due to the low quality of much plastic placed on the market. Virgin plastic production prices are also artificially low, meaning that recycling is often not economically viable.

Zero waste cities could be a key tool in climate change mitigation. Due to high population and resource density, cities are the ideal location for the testing and implementation of zero waste models. Developing bespoke zero waste practices for cities provides local flexibility to respond to local issues and opportunities. Zero waste cities could be one of the quickest and most affordable ways to reduce global warming and stay below 1.5C. The development of zero waste cities should be a priority as, by 2050, two thirds of the global population will live in cities. After buildings and transport, waste is the largest source of emissions in cities. The benefits of zero waste cities extend beyond waste prevention and climate change mitigation. These include:

- Lower waste management costs, especially beneficial as landfill space is becoming scarcer, while incineration projects present toxic and climate-polluting false solutions to zero waste.

- Improved food and energy security and material resilience, as raw material dependence decreases, surplus food can be redistributed to alleviate poverty, and organic waste can be used to produce compost and energy.

- Great local content and quality in employment, as zero waste employment on average generates ten times more jobs than landfilling or incineration due to the higher labour intensity and local cycling of materials.

- Improved soil quality for agriculture, as food waste is separated and treated for compost, and less residual waste is left to seep into the ground and damage ecosystems. San Francisco, for example, uses an organic waste treatment facility to support over 300 vineyards in the local area.

Examples of best practice in building zero waste cities can be seen in Lviv, Ukraine, the first zero waste city in Ukraine. Despite the ongoing conflict in the country, the citizens of Lviv have consistently led by example in resilience and commitment. Starting in 2016, a zero-waste approach was developed in response to a waste crisis. Six years on, the city has found that this has helped them to reduce dependency on fossil fuels, which is now a matter of national security. This has also helped the city to better provide for refugees through providing meals in reusable tableware. The people of Lviv believe that becoming a zero waste city has taught them resourcefulness and compassion in a trying time. It is hoped that the city’s Road to Zero Scenario will result in a 93% reduction in GHG emissions.